Difference Between Prokaryotic And Eukaryotic Cell

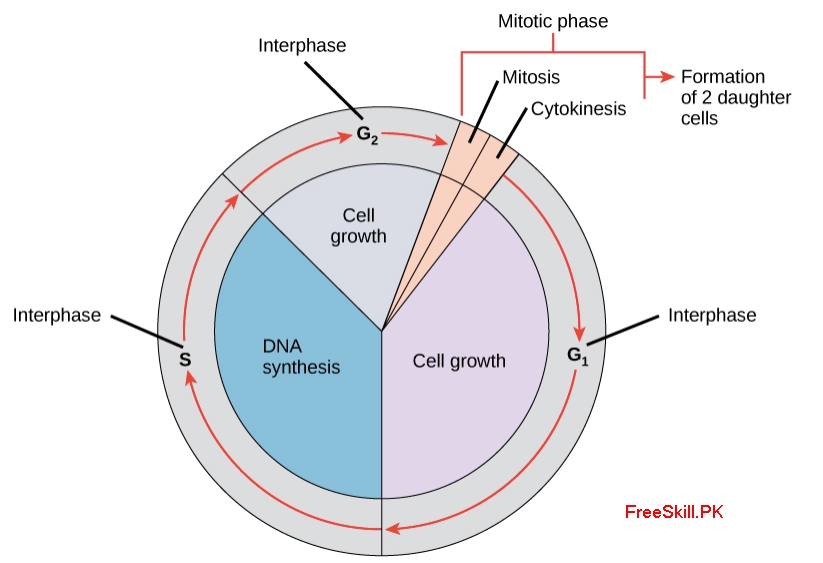

Eukaryotic Cell Cycle is a series of events that occur when cells grow and divide. The cell spends most of its time in the so-called interphase period, during which it grows, mimicking its chromosomes and preparing them for cell division. The cell then leaves the interphase, undergoes mitosis, and completes its division. The resulting cells are called daughter cells, and each enters its own interphase and begins a new phase of the cell cycle.

Function of Eukaryotic Cell Cycle

Because cells proliferate through division, the new “daughter” cells are smaller than their parent cells and can inherit the minimal cellular machinery needed to survive. They need to develop and reproduce their cellular machinery before these daughter cells divide to produce more cells.

The importance of the cell cycle can be understood by performing simple mathematical operations in cell division. If the cell does not grow between divisions, each generation of “daughter” cells will be only half the size of the parent cell. It will be unstable soon!

To complete this development and prepare for cell division, the cell divides its metabolic activity at different stages of Gap1, synthesis, and Gap2 between cell division.

Eukaryotic Cell Cycle Diagram Download

Eukaryotic Cell Cycle Mitosis

In the process of mitosis, the “maternal” cell undergoes a series of complex steps to ensure that each “maternal” cell can get the material to survive, including a copy of each chromosome. After the material is sorted correctly, the “maternal” cell divides the middle and divides its membrane into two.

You can learn more about the detailed stages of mitosis in our article on mitosis and parental cells to ensure that their progenitor cells gain the substances they need to survive. Now, each new “daughter” is an independent living cell. However, they are small, with only one genetic material.

This means that they cannot immediately divide their “daughters”. First, they must go through an “intermediate phase” between the divisions, comprising three distinct phases.

Eukaryotic Cell Cycle Phases

G1 Phase

In the G1 phase, newly formed daughter cells proliferate. People commonly say that “G” means “gap”, because under an optical microscope, external observers consider these steps in cell activity to be relatively passive “gaps”.

However, according to what we know today, using “G” for “growth” may be more accurate — because the “G” phase is a spurt of protein and organelle production, and is actually an increase in cell size. .

In the first “growth” or “gap” phase, the cell produces many essential substances, such as proteins and ribosomes. Cells that rely on particular organelles (such as chloroplast and mitochondria) will also produce more organelles during G1. As cells absorb more material from the environment into living machinery, the size of the cells may increase.

S Phase

In the S phase, the cell replicates its DNA. “S” stands for “synthesis” and refers to the synthesis of new chromosomes from raw materials.

This is a very energy-consuming operation because many nucleotides need to be synthesized. Many eukaryotic cells have dozens of chromosomes — large amounts of DNA — that must be replicated.

During this time, production of other substances and organelles has slowed significantly as the cell focuses on mimicking its entire genome.

When the S phase is complete, the cell will have two complete sets of genetic material. This is essential for cell division, as it can ensure that both daughter cells receive a copy of the “blueprint” necessary for survival and reproduction.

G2 Phase

During G2, many cells also test to ensure that both copies of their DNA are correct and complete. If a cell’s DNA is found to be damaged, it cannot pass its “G2 / M checkpoint”, it is named because the end of the G2 stage contains a “checkpoint”, just the G2 and “M stage” Or between “in mitosis”.

For multicellular organisms such as animals, the “G2 / M outpost” is a very important safety measure. When cells multiply with damaged DNA, cancer occurs that can lead to the death of the entire organism. By testing whether a cell’s DNA has been destroyed before replication, animals and other organisms reduce the risk of cancer.

Interestingly, after synthesizing DNA in S phase, some organisms can completely release G2 and go directly into mitosis. However, most creatures find it safe to use G2 and its associated checkpoints!

If the G2 / M checkpoint is passed, the cell cycle begins again. The cells divide through mitosis, and new daughter cells begin to circulate, allowing them to undergo stages G1, S and G2 to form their new daughter cells.

G0 Phase

For example, neurons — animal nerve cells — do not divide. Their “paternal cells” are stem cells, and “daughter” neuron cells are programmed not to go through the cell cycle because uncontrolled neuron growth and cell division can be very dangerous to the organism.

Therefore, the neuron does not enter the G1 phase after “birth”, but enters a phase that scientists call the “G0 phase”. It is a metabolic state that is used only to maintain daughter cells, not to prepare for cell division.

Neurons and other non-dividing cell types can spend their entire lives in the G0 stage, performing their functions on an entire organism without division or reproduction.

Cell Cycle Regulation

The organism must be able to inhibit cell division when the corresponding cells are damaged or there is not enough food to support new growth. They also need to be able to initiate cell division when growth or wound healing is required.

To do this, cells use various chemical “signal cascades”, where multiple links in the chain produce complex effects based on simple signals.

In these regulatory cascades, a single protein can alter the functions of many other proteins, causing extensive changes in cell function or structure.

This allows these proteins (such as cyclin and cyclin-dependent kinesis) to act as “stop points”. If the cyclin or cyclin-dependent kinase does not function, the cell will not be able to enter later stages of the cell cycle.

See Also: